- Visibility 19 Views

- Downloads 5 Downloads

- DOI 10.18231/j.johs.2024.017

-

CrossMark

- Citation

Demystifying intraosseous mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the mandible: A rare case report integrating cone beam computed tomography insights

- Author Details:

-

Nidhi Yadav *

-

Ajay Parihar

-

Prashanthi Reddy

-

Saloni Agrawal

Introduction

Salivary carcinoma, representing 3 to 4% of head and neck cancers, has garnered significant attention. Among these, mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC) emerges as the most prevalent subtype, exhibiting diverse clinical behaviours, from slow-growing to highly metastatic tumours. Predominantly, MEC affects larger salivary glands like the parotid, while in minor salivary glands, it commonly manifests on the palate, followed by other sites such as the retromolar gap, buccal mucosa, tongue, lips, floor of the mouth, sinuses, and larynx. Intraosseous mucoepidermoid carcinoma, originating in the gnathic bones, has long intrigued researchers due to its rarity. Theories about its origins, stemming from the neoplastic transformation of epithelial mucosa or ectopic salivary tissue, have circulated, yet its precise source remains uncertain.[1] In 1963, Bhaskar[2] studied mucoepidermoid tumours’ origin and composition. In 1991, the WHO renamed "mucoepidermoid tumour" to "mucoepidermoid carcinoma."[3] Waldron and Mustoe[4] later proposed including intraosseous mucoepidermoid carcinoma in primary intraosseous carcinoma of the jaw as type 4, enhancing our understanding of this neoplasm. ([Table 1])

Imaging is crucial for detecting and distinguishing intraosseous mucoepidermoid carcinoma (IMC) due to its distinct features, such as a sclerotic periphery and a mixed internal structure. This structure often presents as a unilocular and/or multilocular pattern, sharing imaging characteristics with other lesions like ameloblastoma, glandular odontogenic cyst, and keratocystic odontogenic tumor. This case report emphasizes the significance of CBCT in accurately delineating the lesion and devising suitable treatment plans for IMC.

Case Description

A 55-year-old woman presented to the Oral Medicine and Radiology Department with a complaint of painful swelling in her lower left jaw, which had persisted for the past three months. The swelling had gradually increased following dental procedures, including the extraction of teeth 36 and 37 and the removal of a cyst a year prior. She had no significant medical history. After two weeks on medication following her hospital visit, a general examination revealed that she had a normal gait, build, and well-nourished appearance with normal vital signs.

|

Types |

Neoplasm |

|

Type 1: |

Intraosseous Carcinoma originating from odontogenic cysts |

|

Type 2A: |

Malignant form of ameloblastoma |

|

Type 2B: |

Ameloblastic carcinoma originating de novo, from ameloblastoma, or from odontogenic cysts |

|

Type 3: |

Intraosseous Carcinoma arising de novo |

|

a) Keratinizing |

|

|

b) Nonkeratinizing |

|

|

Type 4: |

Intraosseous mucoepidermoid carcinoma. |

|

Lesion |

Age/Gender |

Common Site |

Clinical signs |

Radiological Features |

|

Ameloblastoma |

Age 20-50, avg. 40, male. |

Posterior Mandible |

Asymptomatic, but may show bone expansion |

Soap-bubble, honeycomb, or tennis-racket patterns, with spared and expanded cortices. Knife edge root resorption. |

|

Odontogenic Keratocysts |

Age 10-40, Male |

Posterior mandible |

Asymptomatic, without cortical expansion. Paraesthesia may occur in advance stage. |

Curved internal septa can form a multilocular appearance; growing within medullary space and may cause tooth displacement without root resorption. |

|

Odontogenic myxoma |

10-50 (average 25-35), No gender predilection |

Posterior mandible |

Asymptomatically or with nonspecific symptoms such as swelling, pain, or tooth displacement. |

Soap-bubble, honeycomb, or tennis-racket Fine intralesional trabeculation common, -Tooth displacement: Often occurs, with potential mobility Rare; minimal tooth root resorption with considerable expansion |

|

Central giant cell granuloma |

Under 30 years of age, Female |

Mandible anterior to the molars. |

Slow-growing, painless, expands and thins cortical plates, rarely perforating into soft tissue. |

Granular bone pattern forms wispy striations at right angle or septa, Expansion, tooth displacement and root resorption may be seen. |

|

Squamous cell carcinoma |

30-40 years |

Mandible |

Ulcerated region with central depression and irregular shape. |

Radiolucent area with fuzzy borders (moth-eaten appearance). |

|

Aneurysmal bone cyst |

Under 20 years of age |

Posterior mandible |

Slowly expands, thins cortical plates, rarely destroys them. May cause mild tenderness, tooth displacement, but root resorption is uncommon. |

Soap bubble, circular or "hydraulic" in shape, with wispy septa forming multilocular appearance. Can displace and resorb tooth roots. |

Externally, there was mild facial asymmetry on the left mandibular side due to a diffuse swelling measuring approximately 3 by 4 cm, extending from the mandibular body to the ramus. The swelling had a bony hard consistency and was non-tender upon palpation. Additionally, the left submandibular glands were enlarged and tender.

Intraorally, a diffuse, bony hard, and tender swelling measuring approximately 3 by 4 cm was noted, with dilated vessels over its surface. This swelling involved the ramus and mandibular body from the second premolar region onwards, causing obliteration of the buccal vestibule and extending from the alveolar ridge to the inferior border of the mandible. Mild expansion of the buccal and lingual cortices was observed ([Figure 1]).

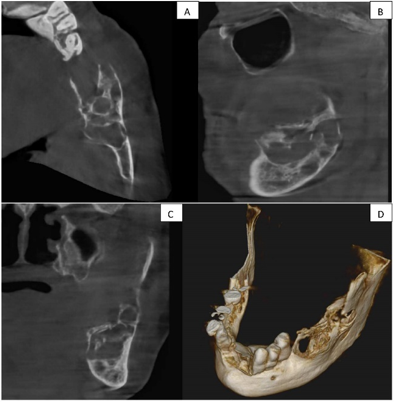

Panoramic radiography revealed an irregular, lobulated, expansile osteolytic lesion, approximately 3 by 4 cm in size, extending from the distal aspect of the second premolar to the ramus and coronoid process posteriorly. Based on the clinical examination, the provisional diagnosis was a residual cyst ([Figure 2]). Lab findings showed hemoglobin at 10.6 gm%, random glucose at 123 mg/dl, with other parameters being normal. Further investigation with a cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) of the mandibular region showed a single, well-defined hypodense lesion with septate in the left side of the mandibular body and ramus. The lesion spanned antero-posteriorly from the area of tooth 36 to the ascending ramus, leading to the expansion and thinning of the lingual and buccal cortical plates. Measuring approximately 43.1 mm anterioposteriorly, 16.2 mm bucco lingually, and 17.5 mm superioinferiorly , it had an irregular shape with a multilocular appearance internally. The surrounding structures displayed a discontinuity in the superior border of the inferior alveolar canal in the regions of teeth 37 and 38, alongside significant thinning and expansion of the lingual cortical plate. The buccal cortical plate was discontinuous in regions 36 and 37, and thin and expanded elsewhere, while the inferior border of the mandible appeared intact ([Figure 3] a, 3b, 3c, 3d). The radiographic differential diagnosis was considered as ameloblastoma, odontogenic keratocyst, odontogenic myxoma, aneurysmal bone cyst, and central giant cell granuloma explained in detail. ([Table 2])

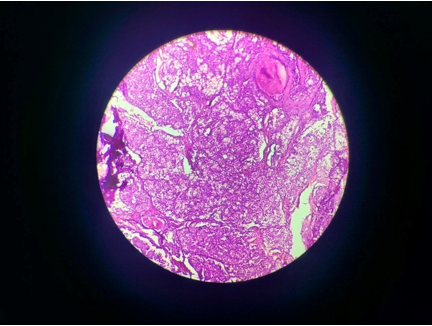

Finally, an excisional biopsy was performed, and histopathological examination revealed the presence of a glandular component with severe dysplasia, epidermoid cells, intermediate cells, and mucous cells along with disintegrated bony trabeculae, suggestive of intraosseous mucoepidermoid carcinoma ([Figure 4]).

Discussion

In 1945, Stewart and colleagues provided a detailed description of the mucous-secreting and epidermal cellular components of a specific pathological condition, establishing it as a distinct entity.[5] Additionally, Lepp's 1939 report[6] on the first case of intraosseous mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC) of the mandible ignited further investigation into its histological makeup and how tumors of this type develop. IMC is a rare bone tumour with only 136 reported cases in English literature since its first description.[7]

The mandible, particularly its posterior section, is frequently where intraosseous MECs are found. This condition affects women more often than men, and although it typically occurs in individuals aged between their fourth and fifth decades, cases have been documented in patients ranging from their first to seventh decades. Our cases align with the patterns observed in existing literature. Common symptoms of intraosseous MEC include painless swelling in the oral cavity, pain, tingling sensations, numbness, and loose teeth.[8]

Etiopathogenesis

The etiology of this lesion remains uncertain, yet various theories attempt to elucidate its origins. Potential explanations include:

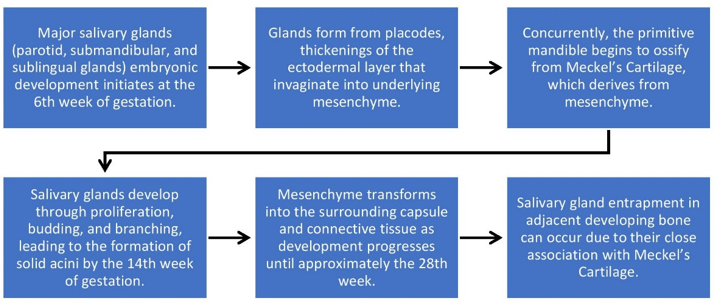

Persistence of ectopic salivary gland tissue, remnants of embryonic salivary glands entrapped within bone.

Transformation of mucous cells present in odontogenic cysts.

Intraosseous extension of maxillary sinuses or submucosal and mucosal glands.[9]

An alternative interpretation posits the integration of salivary glands into the developing mandible.[10] ([Figure 5])

However, Imaging is crucial for detecting and distinguishing MEC due to its sclerotic periphery and varied internal structure, resembling patterns seen in other lesions like ameloblastoma, Odontogenic keratocyst, odontogenic myxoma, Squamous cell carcinoma, Central giant cell granuloma and aneurysmal bone cysts. According to Chan et al, [11] radiographic features of the IMC include well- defined sclerotic margins with an amorphous internal sclerotic bone and several minor locules. Additionally, the aggressive nature of the tumour showed by cortical bulging, perforation of the cortical bone, and invasion of the tumour to surrounding soft tissues, with the displacement of the tooth and root resorptions.[7] Brookstone and Huvos[12] proposed a three-grade classification for IMC:

Grade 1: Absence of cortical plate expansion or rupture.

Grade 2: Cortical plate expansion occurs without rupture.

Grade 3: Cortical plate rupture or presence of regional metastasis.

However, panoramic radiography does not allow as assessment of destructive bone lesions with non-uniform border or with degrees of extension and invasion into the surrounding tissues, nor enough to differentiate this kind of tumour from an odontogenic cyst or ameloblastoma. On the other hand, CT offers a large amount of information on size, location, and area of the tumour in the region.[13] Diagnostic criteria for intraosseous MEC were defined by Alexander et al. and modified by Browand and Waldron and are as follows:[14]

Intact cortical plates on CT

Radiographic evidence of bony destruction

Exclusion of another primary tumor whose metastasis could histologically mimic the central tumor

Exclusion of an odontogenic tumor

Histopathologic confirmation

Detectable intracellular mucin

These lesions are typically treated with radical resection of adjacent normal bone margins. In some cases, neck dissection and post-operative radiation therapy are necessary. In our case, the lesion was treated with radical resection followed by adjuvant radiotherapy.

Conclusion

This case emphasizes the importance of recognizing and managing malignant tumors arising from odontogenic cysts. Thorough surgical intervention, supplementary treatments, and histopathological analysis are crucial. CBCT helps differentiate intraosseous Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma from primary dentigerous tumors, facilitating timely diagnosis and treatment planning, ultimately enhancing patient outcomes.

Source of Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- GB De Freitas, A De França, ST Santos, MO De Lima Júnior, AS Da Fonte Neto, P Bernardon. Intraosseous Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma in the Mandible. . Case Rep Dent 2018. [Google Scholar]

- SN Bhaskar. Central mucoepidermoid tumors of the mandible. Cancer 1963. [Google Scholar]

- G Seifert, LH Sobin. In International Classification of tumours. 2. New York Springer-Verlag;. Histological Typing of Salivary Gland Tumours 1991. [Google Scholar]

- G Thomas, A Mathew, M Pandey, EK Abraham, A Francis, T Somanathan. Report of two new cases and pooled analysis of world literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2001. [Google Scholar]

- WG Shafer, MK Hine, BM Levy. . Text book of Oral Pathology 1974. [Google Scholar]

- H Lepp. Zur Kenntnis des papillar wachsenden schleimigen cystadenokarzinoms der mundhohle. Zieglers Beitrage Z Pathol Anat 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Rrk Saripalli, A N Jakkula, Lsc Alluri. . BMJ Case Rep 2022. [Google Scholar]

- B Başaran, C Doruk, E Yılmaz, E Sünnetçioğlu, B Bilgiç. Intraosseous Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma of the Jaw: Report of Three Cases. Turk Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2018. [Google Scholar]

- B Johnson, I Velez. Central mucoepidermoid carcinoma with an atypical radiographic appearance.. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathology, Oral Radiol Endodontol 2008. [Google Scholar]

- JA Phero, E Hannan, R Padilla, T Turvey. Ectopic salivary tissue of the mandibular condyle: A case report and review of the literature.. Oral and Maxillofac Surg Cases 2020. [Google Scholar]

- KC Chan, M Pharoah, L Lee. Intraosseous mucoepidermoid carcinoma: a review of the diagnostic imaging features of four jaw cases. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2011. [Google Scholar]

- MS Brookstone, AG Huvos. Central salivary gland tumors of the maxilla and mandible: a clinicopathologic study of 11 cases with an analysis of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Alf Costa, T Ferreira, HA Soares, Acr Nahas-Scocate, G Montesinos, PH Braz-Silva. Cone beam computed tomography diagnostic imag . Cone beam computed tomography diagnostic imag ing of intra-osseous mucoepidermoid carcinoma in the mandible. J Clin Exp Dent 2017. [Google Scholar]

- RW Alexander, RH Dupuis, H Holton. Central mucoepidermoid tumor (carcinoma) of the mandible. J Oral Surg 1974. [Google Scholar]